Competition and Reflection

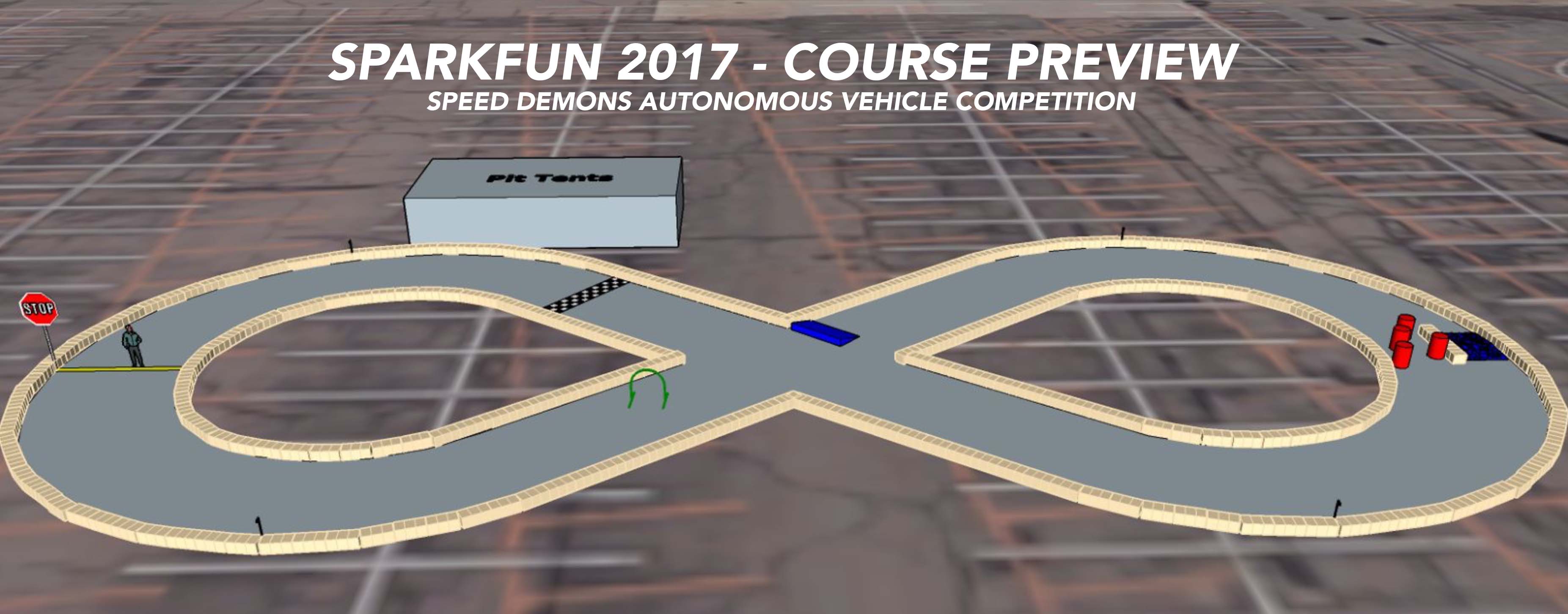

This page is dedicated to sharing our competition experience and reflection. A course map of the competition is shown above for reference. For those interested in the competition rules, please visit SparkFun’s official site for the SparkFun’s 2017 Speed Demons Autonomous Vehicle Competition rules.

Topics

Competition Synopsis and Reflection

After completing the competition, we sent an email to the board members of the IEEE Branch of the University of California, San Diego, whom have funded and supported us throughout the way, to relay the news regarding what happened during the competition day. Looking back, we believe that this email accurately captures the synopsis and sentiment of the team on the competition day. Below is the email sent to the board members on October 16, 2017:

Hi all!

We’ve recently came back from the competition on Sunday and the official scores have just been announced this morning. We placed #1 in the higher education category and #2 overall!! As a reward for being #1 in the higher education category, UCSD IEEE will be receiving a LulzBot Mini 3D Printer.

Scoreboard: https://avc.sparkfun.com/2017/scores

Official Announcement: https://avc.sparkfun.com/blog/2503Team Reflection

I am actually really proud of us as a team throughout the whole year. We had two hardware members (Jason Kelley - Electrical) and (Jack Wheelock - Aerospace) who were really responsive and on top of it throughout the entire year. They created a custom 360 LIDAR sensor, power regulator, and a lot of 3D molds that improved the car’s stability (shock absorbers, base, mount, etc). It was quite shocking to see how much on the hardware side was accomplished by just the two of them.

On the software side, we had four members: Jason Ma, William Ma, Shirley Han, and Peter Mai. We’ve met twice every week throughout the entire 2016/17 school year. And I believe what really allowed us to be #2 overall this year was that the team was doing 40 hrs/week during the last 3 weeks of summer, and 24 hrs/week during week 1-2 right before the competition. I am really impressed by the amount of dedication the whole team has placed into this project and it really couldn’t have happened without everyone’s continual contribution and support.

Competition Test Day Experience

We arrived to the competition site in Denver, Colorado on Friday October 13, 2017, for testing from 12 PM - 8 PM. That was when we noticed a new unannounced obstacle that would have prevented our car from ever completing the course. The pedestrian on the course actually moves back and forth. Which isn’t really an issue for our car as it computed its path all dynamically in real time at 10 times a second. The real issue was that to make the pedestrian move, they built a ramp around him that all cars had to pass.

When we designed our car, it was built to only run on flat surfaces with no uneven terrain. Because we used a 360 LIDAR, we had a 2D map of the environment around us that was parallel to the ground. But since the ramp we had to cross was higher than our car, our sensor now saw the ramp as a wall, a dead end. We spent half of the day working on this problem and decided that we were going to angle our LIDAR so that it is at an incline, where the front was tilted slightly up. This allowed us to see pass the ramp (no longer a wall), while still seeing tall obstacles, with the cost of not being able to see very far out because our 2D plane was no longer parallel to the ground. Cool, we’ve made it up the ramp. Now going down, the front of the LIDAR sees the ground. Another wall! Man, uneven terrains do not go well with 2D 360 LIDAR at all. To not bore you all, we found a solution for that as well. There were a few other minor navigation issues that we’ve spent the rest of the day working on.

By the end of the day, we had a good feeling that our vehicle would be able to complete the course. We’ve set up the obstacles on the course that were way under the minimum 3 feet clearance and just set our car to run forever around the course. It was able to complete the course 70%-80% of the time.

Minor issue. The judges told us we needed a button to start the car and cannot do it through SSH. We didn’t have any buttons, but we did have two Arduinos. However, the only button on the Arduino was the reset button. We spent the whole night hacking to make that work and we eventually connected two Arduino Nano together, making one of the reset button a programmable button that sent a signal to the other Arduino. Both had to be powered by two separate power supply to work correctly. Got it to work. Next day, change of plan, turned out we didn’t need a button after all.

Competition Race Day Experience

This was probably one of the most stressful time for the team as we witness our one year’s worth of effort unfold. We did a few practice run in the morning and the car was able to complete all of it. However, the pedestrian was never moving in these test runs.

HEAT 1

On the first heat, our car made it past the barrels, avoiding other cars while doing so, went through the intersection without making any turn, made it through the hoop, and past the ramp with the pedestrian. With the finish line only a few meters out with no obstacles ahead, we were eagerly anticipating our first successful heat. But, the car had a mind of its own… U-TURN…. back into the pedestrian. WHYYY… We were really confused why it would do this and really had no clue as this never happened in the past. However, our car made it the furthest out of everyone on that first heat, scoring the team 65 points.HEAT 2

During the 20 minute break time, we tested the vehicle again, asking the judge to have the pedestrian on. The car still was able to make it by every single test with no hiccup. Befuddled, we placed the car down for its second race, with no change in code, hoping that it was due to a very rare hiccup in our code. As the car ran off, it dodged all the early vehicles, weaved its way through the barrels, continued for a long stretch, avoided the ramp, made it past the intersection, through the hoop, to where it once again must face the moving pedestrian on the ramp. Heart racing, the car attempted to make it up the ramp as the pedestrian crossed right in front of it. It passed without a glitch! Off the ramp it goes and all of a sudden… RIGHT TURN into the hay bales. Oh wait.. it’s backing up, it’s going towards the pedestrian again. U-TURN mode kicks in. Phew! The car is reorienting itself to the correct path. There is hope!! The crowd cheers on. But no… it over compensated in its reorientation. Trying to reorientate a second round, it finds itself again at the bottom of the pedestrian ramp going in the opposite direction. As the LIDAR is angled forward, the car believes there are no obstacles ahead and tries to make a U-TURN while going up the ramp. Stress level high. Could the car correctly reorientate itself? Detecting that the car is now at an uphill battle, it increased the throttle to get itself up. A little too much power, the car has now ran off the race track. RIP car. So close yet so far. Regardless, we did make it furthest again on this second heat, giving the team an addition 65 points for a total of 130 points, highest of any team so far.HEAT 3

While reviewing our video recording of the car’s run, we noticed that while going up and down the ramp as the pedestrian crosses, the car had to very quickly turn to avoid the pedestrian and turn back to get itself in the correct straight path. Combine this quick movement with going up and down the ramp, our yaw reading of the car no longer represented the true yaw the car took. This confused our navigation module that was in charge of detecting if the car U-turned and needed to reorientate back to the previous straight forward direction. What to do.. we only had 20 minute to implement, test, and deploy code. This was the last race we had. It’s all or nothing. There is no room to mess up. How good are our problem solving and coding abilities?? Stress level peaking. There was no time to panic.We decided to stop tracking the car’s IMU orientation when it is not on a 0 degree incline surface. Going off the ramp, the car would set its history of IMU orientations to the car’s current orientation. This ensured that the car would not U-turn of the ramp as its past orientations all indicated that it’s going the same direction. Coded. Tested. Deployed!

Round 3 starts now. 3, 2, 1, GO! We quickly noticed that the other competitors had fine tuned their code too. There were two cars going neck to neck with us. Oh boy. Three cars heading towards the first obstacle. Barrels on one side, and an impossible obstacle ramp on the other side. There are so many ways our race could end here.

1) Our car detects other cars in the barrels and decides that it’s a dead end as there’s no room and takes the high route onto the obstacle ramp, which the car’s physical structure was not designed to tackle. 2) The other cars crashes and knocks over the barrels and we can’t get pass. 3) The other cars are stuck in the barrels and we can’t pass.

One by one, each of the three car weaved its way through and made it out in a single file line! Crowds are cheering. Out of the barrels, one car crashed into the wall. Now there’s two. Us versus another car. Going neck to neck, side by side, this was one of the closest race we’ve witness yet. Passed the intersection. Hoop laid ahead. Both cars wanted to go through it. Our car made it through, and the other car suddenly decided to ram us hard on the side of our vehicle! Our car stopped. No!!! The other car continued without looking back and finished, being the first car to complete the course. Meanwhile, our car stayed at a standstill at the hoop. LIDAR was still spinning. All vehicle lights were still on. The car was not dead. It stayed there for another 30 seconds. We thought the other car may have knocked off our steering Arduino USB connection, as this would be the only way our car would stop. However, from a far, everything still seemed to be in tact. The car does have a module that detects any anomaly in sensor readings and attempt to restart itself. But that should have happened by now. Super disappointed and unsure of the state of the car, we were about to call off the race. But no, the car kicks off again! Vroom, it makes it past the pedestrian ramp. No U-turn this time, and into the finish line! What are the chances?!?!

Passing all the obstacles gave us 65 points, finishing gave us a time bonus of 181 points and a no GPS bonus of 150 points. The total points awarded for that round came out to be 396 points, giving us a combine score of 526 points after the three heats, and placing the team at #1 overall at the end of the first competition day.

But now the real question.. what happened to the car. Our steering Arduino was connected to ROS on the Nvidia Jetson. When the other car ram into us, for a split second, it interrupted our USB connection. This caused the Arduino to loss sync with the main ROS driver module. Unsure of the command to send to the ESC/steering, the Arduino stopped the car as a safety measure. The Jetson should at this point detect that it has lost sync with one of its connection and attempt to reconnect by restarting the connection. This in the past only took a few seconds. During the race however, this took longer than usual. The impact was on the side of the car and was a direct hit to the USB hub and Arduino connection. This was the hardest hit to the side the car had ever encountered, as when testing, the car would only hit in the front. If the connection was still in tact, the Jetson should detect this and once it recognizes a secure connection, it should reattempt to sync up the connection to ROS master. The long time it took to do so, we are not sure why. But it was an expected behavior for the Arduino to reconnect if this was indeed the case, just not this long in between.

Competition 2nd Day

We were not here to witness the second competition day. But after the competition, there was only one team that beat our score. Making us #1 in the higher education category and #2 overall.

Competition Overall Reflection

Reflecting back, I think the team is really proud of their accomplishment, and they should be. We believe that our car could have completed all three runs with no issue. But given the fact that there was an obstacle, moving pedestrian ramp, that was never specified in the documentation, and that we had one day to implement, test, and deploy code on the spot. This was a very big task to tackle and the fact that team was able to pull it off in such a time constraint was a miracle. Also, starting from just a car chassis, to learning ROS with no help, interpreting custom 360 sensor, to ditching Hector SLAM for our own custom navigation modules (just a minor few thousand lines of code) is an incredible feat to accomplish and the team has successfully pulled it off. We came back from the competition very drained and mentally incapacitated, but if one thing was certain, the team was very proud of what they have accomplished this year. No longer stressed, we can look back and say that this was one of the most challenging and rewarding competition we have participated in, where most things were built and designed entirely from scratch with no mentor nor help.

Future Design Changes

Through given this opportunity to build a fully autonomous obstacle avoiding race car, we were able to learn a ton on both the inner workings of the hardware and software side of an autonomous system. If we were given the chance to build a version 2 of our vehicle, we would start off by tackling some of the shortcomings of our vehicle.

One of the major drawback of our vehicle’s design using a 2D LIDAR was that the vehicle was only able to operate on perfectly flat terrains. If we were going into this project again, we would add a new primary sensor that would be able to detect depth in 3D space, such as the ZED Stereo Camera created by Stereo Labs. By having a 3D (point cloud) map of the environment, we would be able to further analyze the surrounding and determine the incline of the terrain at different point in the map and distinguish the difference between terrain incline change (ramp) versus a wall/obstacle.

Another challenge we had throughout the year was not being able to determine the vehicle’s actual speed at given any time. As stated before, since we were sending out percent of max throttle to the ESC, the actual vehicle speed could vary drastically depending on the incline of the surface we are on. This also made it hard when deploying SLAM algorithms as we were unable to give a rough estimation of how far the vehicle had moved in a given time frame, making SLAM fully reliant on comparing present to previous 2D scan frames. We can solve this problem and increase SLAM’s reliability by adding an odometer onto the vehicle. This can be done by measuring the drive shaft’s rotation or wheel’s rotation using a black and white indicator with a photosensor. We can then ensure that the vehicle is going at the specified speed (m/s) using a closed-loop algorithm on the Arduino that is sending out servo commands to the ESC.

In addition to that, SparkFun AVC and the autonomous system industry in general is gradually moving more and more towards incorporating computer vision in their products. Though we have tested the water this year using Haar Cascade to detect certain objects in images, we haven’t actually implemented it in the vehicle for use during the competition. If we were continuing this project, we would implement more image recognition software to further analyze the environment and determine if objects in the environment are people, hay bales, other vehicles, stop signs, concrete roads, etc. This information would be beneficial in helping us decide if we should go towards or avoid a certain part of the map. In the case where another vehicle is blocking the road, knowing that the object is a vehicle could help us decide if we want to wait and let it figure itself out or try and go around it at the risk of it hitting us. We believe that computer vision would open a whole new range of possibilities in the field of autonomous system. What we’ve listed is only a very small glimpse of its full potential.

Finally, though this does not actually improve the vehicle’s capabilities, it was one of those things we wanted to make to help us in our development stages, but never got the chance to: remote control through Xbox controller or iOS/Android app. Throughout the year, we were controlling the vehicle solely through an SSH connection on a separate computer. This was used for starting/stopping the vehicle’s autonomous mode, as well as for manual control via the ROS rqt_robot_steering GUI, which was not exactly the easiest to do. By having a dedicated app or handheld controller, we can easily start/stop a vehicle and have much more precise manual control over the vehicle’s throttle/steering.